The Guided Walk on the History of Anarchism in Barcelona is an educational project designed to encourage and support anyone interested in learning about working-class history and the key role that anarchists and anarchism have played in it. During the walk, we will discuss key events and figures and explore how anarchism has inspired both workers’ and communities’ social struggles and an emancipatory vision of a free society. Before joining the walk, please read this short introduction, which offers background on the relationship between Barcelona, Catalonia, and Spain—a relationship that made the city a site of social and urban conflict throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, and fertile ground for the reception of anarchist ideas.

People interested in anarchism often first learn of the movement’s important role in the Spanish Civil War (July 1936 – April 1939) and the anarchist social revolution that unfolded in Barcelona and beyond (1936-1937). Throughout the war the Nationalists had the active military support of the fascist regimes of Hitler in Germany and Mussolini in Italy. By contrast Europe’s democratic states, significantly France and Britain, along with the United States, had a policy of non-intervention which effectively blocked the Spanish Republican government from purchasing weapons internationally. Leaving the Republic dependent on the USSR and Stalin for arms. It is worth noting that Mexico was also among the few countries to support the Republican side. The politics of organising and arming forces in defense of the Republic took its toll, and were a constant source of conflict among the anti-fascist forces. This fragmentation was a weakness that ultimately played into the hands of the fascists and the military and was an important factor that contributed to the defeat of the Republic with Franco declaring an end to the war on April 1st 1939. Despite the courageous solidarity shown by the many international volunteers that travelled to join the fight against fascism, the democratic states of Europe and the United States failed the people of Spain, making the Spanish Civil War one of the great historical tragedies of the 20th century. It is reasonable to say that the politics of appeasement afforded Europe’s fascist regimes time to expand their military capabilities and Franco’s success emboldened them. Hitler’s Germany invaded Poland in September of 1939 marking the beginning of World War Two.

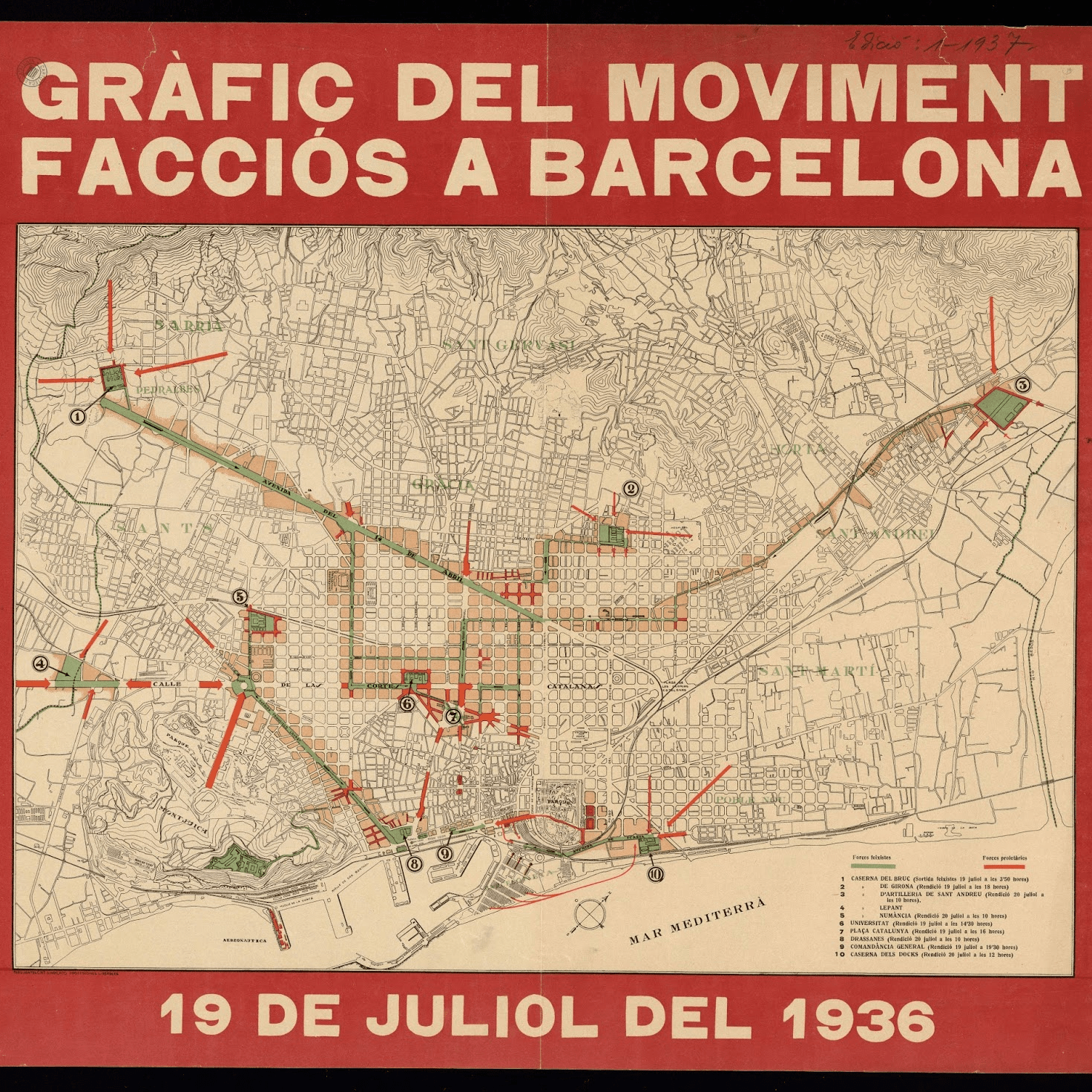

The civil war began on July 17, 1936, when nationalist rebels within the military launched a coup against the Republican government. Early in the conflict, airlifts from Germany and Italy successfully transported thousands of rebel soldiers and arms from North Africa to Spain. Fighting was particularly intense in the south, and the loyalty of military units across Spain was uncertain. Early on July 19, Nationalist generals and soldiers stationed in Barcelona launched their offensive to seize the city. The military outnumbered the Republican police forces and expected a quick victory, but they met massive resistance—most notably from the city’s working class, the majority of whom were organized through the CNT (Confederación Nacional del Trabajo), the anarchist syndicalist trade union, and the militant anarchist FAI (Federación Anarquista Ibérica). After two days of intense fighting, the military was defeated in Barcelona. The anarchists had established barricades and controlled the streets; they had the numbers and the force of arms, giving them effective control of the city. What remained of the Republican government was in no position to challenge them. Barcelona entered a revolutionary moment, and despite the civil war, a social revolution unfolded.

While the guided walk begins and ends with the opening days of the Spanish Civil War, it does not delve into the war itself. Instead, the walk invites you to reflect on what made the revolutionary anti-fascist resistance of July 1936 possible. To do this, we will look at key moments in the historical development of the anarchist movement in Barcelona.

In the 1870s, Catalan and Spanish workers organized to join the International Working Men’s Association. From this period onward, anarchism took root as the anti-authoritarian form of socialism that became popular among the working class in Catalonia and Spain. Several factors made Spain—and Catalonia in particular—fertile ground for anarchism.

1714

The Catalan national day, La Diada, is celebrated every year on September 11. It commemorates the resistance to—and the historic defeat of—the Catalans following the 13-month Siege of Barcelona by Spanish and French forces. This marked the end of the Spanish War of Succession, a struggle over competing claims to the Spanish throne and part of a broader European conflict between the Bourbon and Habsburg dynasties. The Catalans had sided with the Habsburgs, and for this they were punished. The defeat and the events that followed profoundly shaped the historic relationship between Catalonia and Spain, and continue to do so today.

Before 1714, Catalonia was a principality, part of the Crown of Aragon and of the wider Spanish monarchy. However, it had its own political, juridical, and economic institutions and considerable autonomy over them. The new Bourbon king, Philip V of Spain, was determined to punish the Catalans, and in 1716 he introduced the Nueva Planta Decrees.

The king ordered that Catalonia’s historic political institutions to be dismantled. Among these were the Generalitat—the regional parliament, equivalent to today’s Catalan parliament, which retains the same name. In Barcelona, the Consell de Cent, the equivalent of today’s City Council, was dissolved. Spanish was imposed as the official language, and political decision-making was transferred from Barcelona to Madrid.

The city was militarized and by law forbidden from expanding beyond its walls. The walls themselves were rebuilt, expanded, and reinforced. A massive military citadel was constructed to house a permanent garrison. Soldiers were not stationed on the walls to protect the city; their guns and cannons were directed inward at its people as a means of social control. In the map below you see militarized city walls and the massive military citadel on the lower left.

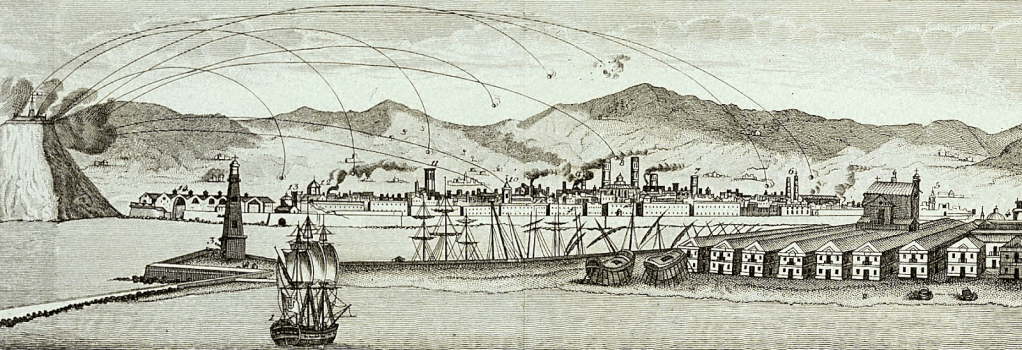

During times of social unrest the city was on a number of occasions bombarded to force its people into submission. In 1842 when a popular revolt forced the military to retreat to the fortress castle of Montjuic, over a thousand projectiles rained down on Barcelona, damaging and destroying hundreds of buildings and taking many lives. For these reasons, the Spanish crown was not particularly popular in Catalonia, and republicanism had a strong political appeal.

For Church and King

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the institutions of Spanish Catholicism and the Spanish Crown functioned as two parts of a single power. Spanish Catholicism has historically had a strongly missionary and militant character. After all, it was the Catholic Monarchs who fought to reclaim the Iberian Peninsula from Muslim rule. The Spanish Inquisition was among the most militant and brutal examples of Catholic reaction against the Protestant Reformation in Europe. Spanish colonialism, too, was justified in missionary religious terms.

It is also important to note that in the 18th and 19th centuries the church administered many of the institutions we associate today with the welfare state. It ran schools, orphanages, hospitals, and prisons, and owned numerous businesses and large properties throughout Spain. Whether a person was a believer or not, the church was present everywhere and part of daily life; the poor and vulnerable were particularly dependent on its institutions. The church preached and defended the crown as the territorial guardian of the Catholic faith, while the crown saw in the church a powerful ally that legitimized its authority not only as morally right but as a divine right.

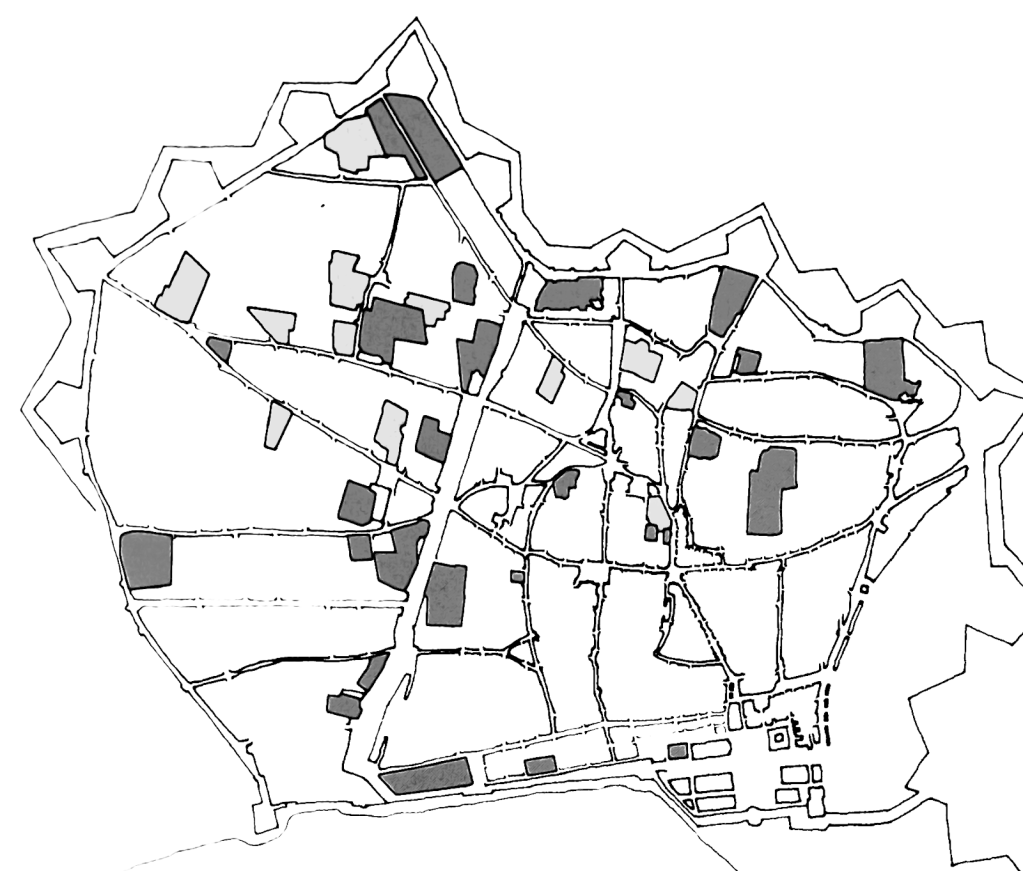

For these reasons the church’s institutions and properties were regarded as potent symbols of power and authority, and during times of social revolt the church was routinely targeted. Readers of Spanish Civil War history often encounter accounts of how the church sided with the military rebels and of the anti-clerical attacks on clergy and church properties throughout Republican Spain. This must be understood in a longer historical context. In Barcelona the church had long been a target of popular frustration during social upheaval and revolt. Among the most well-known examples are la Crema de Convents (the burning of the convents) in 1835 and Semana Tràgica (the Tragic Week) in 1909. This skepticism toward the church’s moralizing authority—manifesting as a popular anticlericalism—was another aspect of Barcelona’s social and cultural life with which anarchist ideas resonated, perhaps best captured in the anarchist expression “No Gods, No Masters.” The image below shows in gray church properties in the city that were targeted during times of social revolt between 1836-1845, many of these sites are today public spaces, cultural centres and markets.

The Industrial Revolution

Geographically well-placed on the Mediterranean coast, Barcelona has historically been a prosperous trading and port city. In the 19th century, Barcelona was the first city in Spain to industrialize. The city experienced rapid industrialization from the 1830s onward, accompanied by an increased demand for labor. As a result, the city became a destination for migrant workers from other parts of Spain, and its population quickly grew to become one of the most densely populated cities in Europe. Rapid population growth in a city that was still, in the 1850s, prohibited by law from expanding beyond its walls meant that, to house this growing population, apartments were subdivided, and workers found themselves in increasingly cramped and overcrowded living conditions. At the same time, the city did not have political autonomy. For the crown in Madrid, distant Barcelona’s urban problems were out of sight and out of mind. It was a recipe for disaster; the overcrowded and unsanitary conditions in the city led to multiple outbreaks of cholera, class tensions, and urban revolt.

In recent years, you may have heard about the movement for Catalan independence in the news. Historically, and certainly in the 19th century, many Catalan republicans advocated for a federal system of government in Spain, aspiring for Catalonia to have greater political autonomy. While Spain today does not have a fully federal system, regions do have a degree of political autonomy. The Catalans played an important role in shaping the demand for this, and it is in part the result of the successful struggles of the Catalans for autonomy during the 20th century.

Why is this important? It is important to understand that even before the popular arrival of anarchism in Spain in the 1870s, there was in Catalonia, for the historical reasons I’ve mentioned, already a critical understanding of problems associated with the centralization of political power. The popular political solution to these problems among Catalan republicans was federalism. The critical questioning of power, authority, and where they rest is central to anarchism. The anarchist solution to the problems and abuses of centralized power is decentralization. Anarchists consider that decisions should be made by those most affected by them, from the bottom up rather than the top down. Anarchist syndicalist unions, for example, organize with re-callable delegates with limited mandates rather than representatives. The idea, in many ways, is simple: that people self-organize through democratic assemblies, in the workplace, but also in communities, and that these then organize at different scales—from the neighbourhood and factory, to the local, regional, national, and international levels —in freely associating federations.

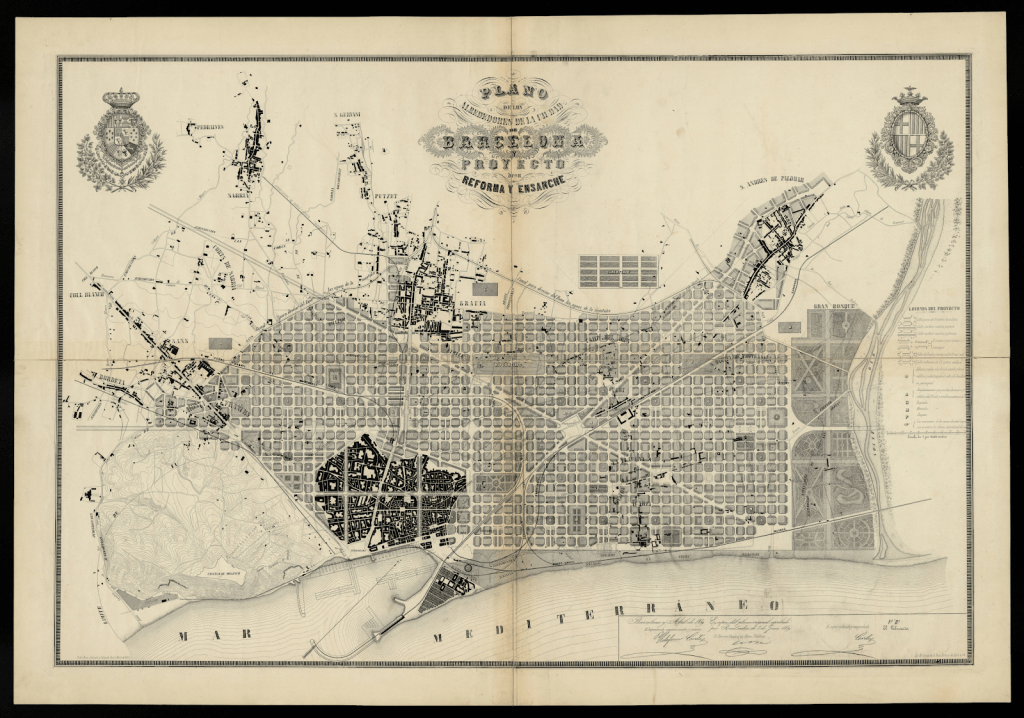

In the 1850s, growing awareness of the crowded and unsanitary conditions in the city, accompanied by the growing political influence of wealthy Catalan merchants and industrialists, led the crown to grant permission for the demolition of the city walls and the acceptance of the famous urban plan of Ildefons Cerdà for the expansion of the city. It is said that the city walls were so hated that once permission for their demolition was granted the ordinary people of the city themselves took up pickaxes to join in its destruction. Cerdà’s plan would take nearly half a century to be realized, but it is the plan that shaped modern Barcelona as we know it today. Cerdà had imagined his plan as a means to address many of the city’s social problems, but the plan would inevitably meet with the realities of conflicting economic and political interests. While Cerdà’s design for the city included green social spaces and inter-class neighborhoods, the real result was that class distinctions were further entrenched as the wealthy moved out of the old town (Ciutat Vella) and into the new neighborhoods of Eixample.

Anarchism as a political philosophy of freedom

Mikhail Bakunin is a critical and important figure in the history of the anarchist movement. We will discuss his role in the International Working Men’s Association and in the formation of the anti-authoritarian international. Many people encounter the works of Marx; far fewer read Bakunin, who was a vocal critic in his time. Anarchism is an emancipatory social vision and a political philosophy of human freedom. To get a sense of Bakunin’s writing, I include below a short excerpt on the topic of freedom from his text “The Paris Commune and the Idea of the State, 1871.”

“Well, then, who am I, and what is it that prompts me to publish this work at this time? I am an impassioned seeker of the truth, and as bitter an enemy of the vicious fictions used by the established order – an order which has profited from all the religious, metaphysical, political, juridical, economic, and social infamies of all times – to brutalize and enslave the world. I am a fanatical lover of liberty. I consider it the only environment in which human intelligence, dignity, and happiness can thrive and develop. I do not mean that formal liberty which is dispensed, measured out, and regulated by the State; for this is a perennial lie and represents nothing but the privilege of a few, based upon the servitude of the remainder. Nor do I mean that individualist, egoist, base, and fraudulent liberty extolled by the school of Jean Jacques Rousseau and every other school of bourgeois liberalism, which considers the rights of all, represented by the State, as a limit for the rights of each; it always, necessarily, ends up by reducing the rights of individuals to zero. No, I mean the only liberty worthy of the name, the liberty which implies the full development of all the material, intellectual, and moral capacities latent in every one of us; the liberty which knows no other restrictions but those set by the laws of our own nature. Consequently there are, properly speaking, no restrictions, since these laws are not imposed upon us by any legislator from outside, alongside, or above ourselves. These laws are subjective, inherent in ourselves; they constitute the very basis of our being. Instead of seeking to curtail them, we should see in them the real condition and the effective cause of our liberty – that liberty of each man which does not find another man’s freedom a boundary but a confirmation and vast extension of his own; liberty through solidarity, in equality. I mean liberty triumphant over brute force and, what has always been the real expression of such force, the principle of authority. I mean liberty which will shatter all the idols in heaven and on earth and will then build a new world of mankind in solidarity, upon the ruins of all the churches and all the states.”

Walk Itinerary

(We do not usually visit all the places listed below. The itinerary is adapted depending on the time available for the walk.If you have some topics of particular interest I am happy to discuss adapting the itinerary.)

- Starting Location: Teatre Principal (Rambla)

Topic: Introduction and overview about the walk. The location was the site of one of the major Anarchist barricades during the fighting in July of 1936. - Location: Plaza Reial (Rambla)

Topic: 1870s The International Workingmen’s Association, the split in the International between those aligned with Marx (Communists) and Bakunin (Anarchists), the development of anarchist syndicalism and the popularisation of Anarchism in Spain. - Location: Liceu Opera House (Rambla)

Topic: 1890s – Insurrectionist Anarchism: Propaganda by the deed, from direct action to targeted assassinations, the bombing of the Liceu Opera House, and the Montjuïc trials. - Coffee Break (Bar Mendizàbal) – https://maps.app.goo.gl/2xQwLVNxzi4LV4c99

- Location: Carrer Carme (Memorial Plaque of the Ateneu Enciclopèdic Popular)

Topic: 1900 – 1909 – Anarchism, secular and working class popular education. - Location: Carrer de Joaquín Costa.

Topic: The 1907 founding of the anarchist syndicalist federation ‘Solidaridad Obrera’ (Worker’s Solidarity). - Location: Porxo de Sant Antoni Abat.

Topic: 1909, ‘The Tragic week’, a historic city wide revolt. - Location: Plaça de Josep Maria Folch i Torres.

Topic: The Prison of Queen Amalia (The Women’s Prison) - Location: Carrer de L’Aurora.

Topic: Plaque in memory of the anarchist Teresa Claramunt. - Location: Rambla de Raval

Topics: The foundation in 1910 of the CNT (National Confederation of Workers). The 1919 General Strike ‘La Canadenca’ which achieved the 8hr day. Pistolerismo (the time of the gun), targeted assassinations against the labour movement. Moderates and militants in the anarchist movement. The founding of the FAI (Iberian Anarchist Federation. - Finishing Location: Maritime Museum

Topics: The Second Spanish Republic. The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. The location is close to the site of Atarzanas Barracks which was demolished, it was the final barracks to fall in the fighting in Barcelona, marking the defeat of the military and the fascists by the anarchists.

Resources and Further Reading

Articles

Anarchism and The First International – Robert Graham

Books

Short History of Anarchism – Max Nettlau

We Do Not Fear Anarchy—We Invoke It. The First International and the Origins of the Anarchist Movement by Robert Graham (Excellent and detailed examination of the evolution of anarchism as both a movement and distinct body of ideas in and through the first international.)

The Spanish Anarchists – Murray Bookchin (A good introduction to the history of Anarchism in Spain)

The Anarchist Inquisition – Mark Bray (On the history of Propaganda by the Deed)

Anarchist Education and the Modern School: A Francisco Ferrer Reader – Mark Bray

Anarchism and the City Revolution and Counter-revolution in Barcelona, 1898–1937 – Chris Ealham (In depth examination of the dynamics of urban transformation and social struggle that contributed to making Barcelona fertile ground for the development of the anarchist movement.)

Durruti in the Spanish Revolution – Abel Paz (A fascinating read and insight into the life and times of the Spanish Anarchist Buenaventura Durruti)

“Forgotten Places: Barcelona and the Spanish Civil War.” by Nick Lloyd (2015).

“Historia del anarquismo en España (1870-1980).” by Josep Termes (2011).

El movimiento obrero en la historia de España. Manuel Tuñon De Lara (1972).

El Raval: Epicentro del movimiento obrero revolucionario barcelonés. Assemblea del Raval (2018).

Breu història de l’anarquisme als Països Catalans. By Dolors Marín Silvestre and Jordi Martí Font (2021). Pagès Editors.

Archives

The Institute for Social History is home to an archive of anarchist historical materials.

https://iisg.amsterdam/en/about/history

LIDIAP is an extensive digital archive of historic and contemporary anarchist publications from around the world.

https://lidiap.ficedl.info/

http://cataleg.xarxabibliosocials.org/portal/

Ateneu Encyclopedic Popular is a historic social and cultural centre in the Raval which has a regular program of events as well as a library and archive.

https://ateneuenciclopedicpopular.org/

Foundations

https://www.ferrerguardia.org/

https://fundacionssegui.org/barcelona/es/fundacion-salvador-segui/

http://www.centrefedericamontseny.org/

Anarchist Bookshops in Barcelona

Rosa de Foc

https://www.cntaitcatalunya.org/llibreria-la-rosa-de-foc

https://maps.app.goo.gl/s1wmJMXZFmuCK78M6

El Lokal

https://ellokal.org/

Maps

https://map.workingclasshistory.com/

Contact Details

If you have any further questions, interested in further reading or sources please feel free to contact me, Caoimín Ó Flannagáin at anarchist.barcelona@gmail.com